The Overlooked Japanese Bonds: Why Japan Could Be a “Ticking Time Bomb” for Global Financial Stability?

TradingKey - After three decades of economic stagnation, Japan’s financial environment is undergoing a significant transformation. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has initiated a tightening cycle through interest rate hikes and reduced bond purchases—triggering volatility in both the yen exchange rate and Japanese government bond (JGB) market.

Since the late 1990s, prolonged monetary easing fueled the rise of the so-called “yen carry trade”, reinforcing the yen's status as the third-largest reserve currency after the U.S. dollar and euro. As a result, movements in the yen and JGB yields have become globally relevant.

Compared to other major bond markets, however, foreign investors have shown limited interest in Japanese debt. With the BoJ absorbing most newly issued bonds under ultra-low or negative interest rate policies, overseas investors saw little incentive to participate. Moreover, global markets had grown accustomed to Japan’s massive debt-to-GDP ratio—now well over 200%—and paid it relatively little attention.

However, the sharp selloff in the Japanese bond market in May 2025 reignited global concerns. What caused the recent surge in JGB yields—and why should global investors care?

Overview of Japan’s Government Debt Market

Japan’s so-called “lost three decades” began with the bursting of the asset bubble in the early 1990s, followed by years of economic stagnation and weak growth.

Each decade since has had its own challenges:

- 1991–2000: Bubble collapse, banking crisis

- 2001–2010: Deflation, QE, early signs of Abenomics

- 2011–2020: Post-earthquake stimulus, ultra-loose monetary policy under Abenomics

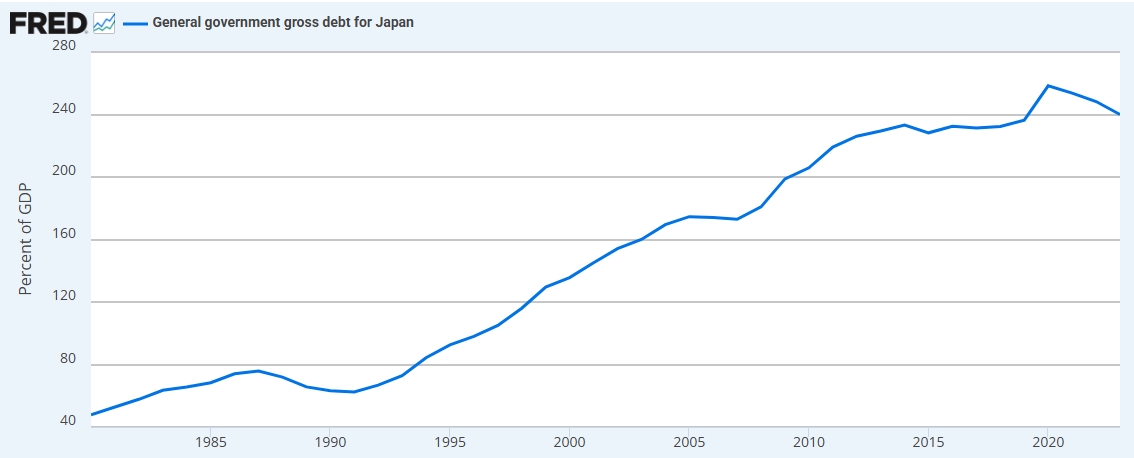

During this period, Japan expanded its fiscal spending aggressively, while the BoJ purchased more than half of all new government bond issuance. Public debt surged—especially during the Covid-19 pandemic—pushing Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio above 230%, higher than Greece at the peak of the European debt crisis.

Japan’s Government Debt, Source: St. Louis Fed

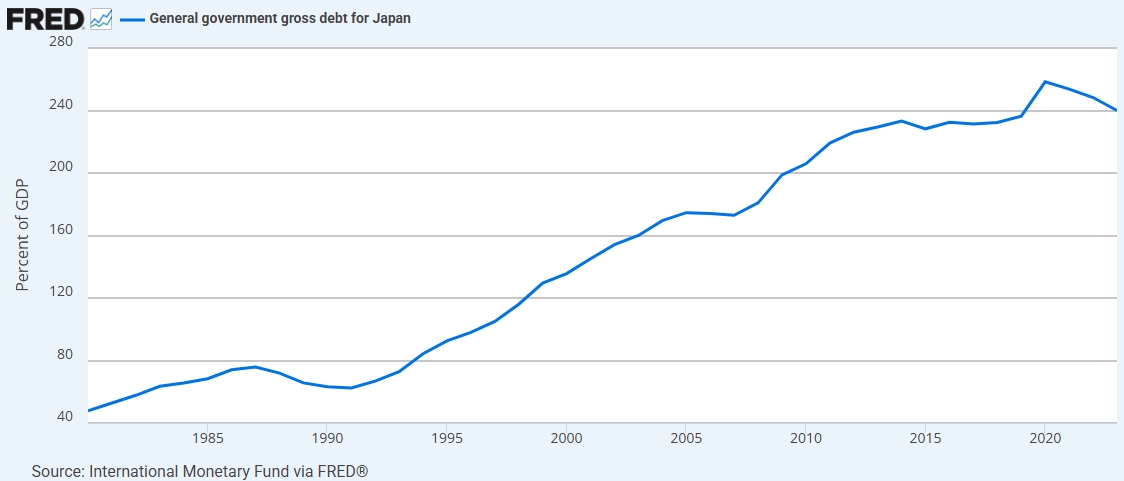

Today, Japan remains one of the world’s most indebted nations:

Japan’s Debt-to-GDP Ratio, Source: St. Louis Fed

Key Features of the Japanese Bond Market:

- Ultra-low yields: Long-term accommodative policies kept bond yields near zero or negative.

- Domestic-dominated ownership: Around 95% of JGBs are held domestically—primarily by the BoJ, insurance companies, banks, and pension funds.

- Deep central bank involvement: Through aggressive QE and Yield Curve Control (YCC), the BoJ became the largest holder of JGBs (52% as of Dec. 2024).

- Limited market liquidity: Due to low participation from foreign investors and heavy central bank control, price discovery and trading activity remain weaker than in U.S. or European markets.

Despite Japan’s massive debt burden, bond prices remained stable for years due to several factors:

- All bonds are denominated in local currency, reducing external default risk

- Low foreign investor exposure prevented capital flight

- Persistent deflation kept interest costs manageable

- High domestic savings supported internal demand for bonds

Why Is the Japanese Bond Market a “Ticking Time Bomb”?

For years, the JGB market flew under the radar—but recent shifts in domestic policy and global financial conditions have heightened sensitivity to changes in Japanese yields.

Some analysts warn that if confidence in Japanese government bonds — long considered a safe haven — collapses, it could trigger a broader loss of confidence across global financial markets.

The risks stem from two key channels:

1. Yen Carry Trade Unwinding

The yen has long been a popular funding currency in carry trades, where investors borrow cheaply in yen and invest in higher-yielding assets abroad—such as U.S. Treasuries or emerging market equities.

This strategy thrived on large interest rate differentials and stable exchange rates. But with Japan ending its era of negative interest rates, the cost of borrowing yen rises — increasing the risk of forced unwinding.

A sudden rise in Japanese bond yields could prompt capital repatriation, leading to a massive sell-off in high-yield assets—including U.S. stocks and Japanese equities.

In August 2024, a similar unwind occurred, causing a global financial tremor—with equity markets across the globe falling sharply.

2. Second-Largest Creditor Nation

Japan has long been the world’s largest creditor nation, though it recently dropped to second place behind Germany, with net foreign assets reaching a record ¥533 trillion (approx. USD 3.4 trillion) by the end of 2024.

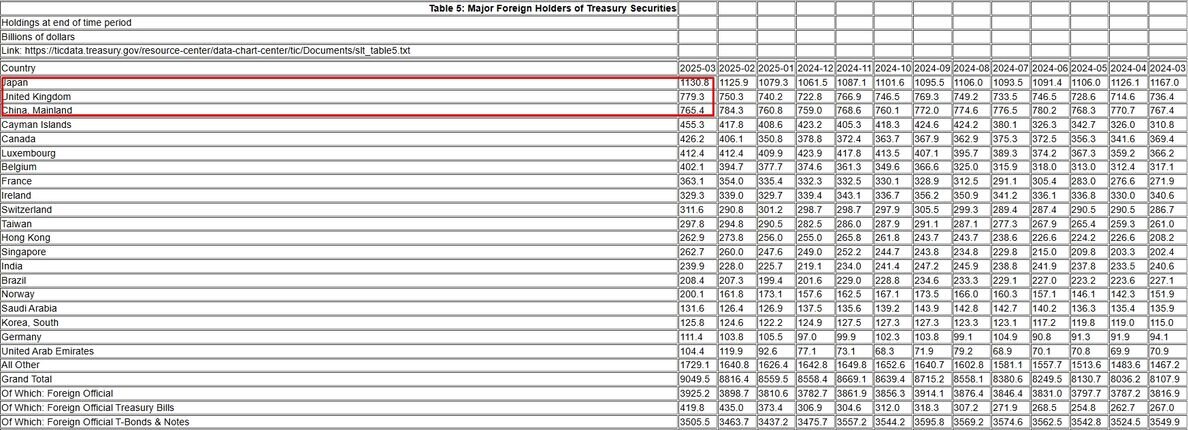

As the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasuries, Japan’s holdings stood at $1.13 trillion as of March 2025, according to the U.S. Treasury.

Major Foreign Holders of U.S. Treasuries, Source: U.S. Treasury

If Japanese investors shift capital back home—attracted by rising JGB yields—it could lead to a large-scale selloff in U.S. Treasuries, triggering systemic risk in global bond markets.

Deutsche Bank, Vanguard, and RBC BlueBay Asset Management have already started adjusting their strategies, recognizing the growing appeal of JGBs relative to U.S. Treasuries.

Morgan Stanley analysts warned that the rising yield on 30-year Japanese government bonds is sending worrying signals to the U.S. bond market.

Why Did Japanese Bonds Suddenly Collapse?

On May 20, 2025, a poorly received 20-year JGB auction served as the catalyst for the bond selloff. The bid-to-cover ratio fell to its lowest level since 2012, signaling weak investor appetite for long-dated debt.

Amid uncertainty around Trump’s tariff policies and a cautious BoJ, the sharp rise in JGB yields came as a surprise.

In summary, Japanese bonds face pressure from both supply and demand :

- Supply side: With Q1 GDP turning negative and worsening fiscal outlook, Japan is expected to increase bond issuance.

- Demand side: The BoJ continues to reduce bond purchases as part of its tightening stance, while global liquidity conditions are tightening—further weakening investor appetite.

The second-largest holders of JGBs—life insurance companies—are not stepping in to fill the gap. Goldman Sachs noted that life insurers are facing a negative duration gap, making them reluctant to absorb additional long-term bond risk.

Under current conditions, an increase in long-bond holdings would cause asset depreciation, offsetting gains from liability-side adjustments—prompting some institutional buyers to become sellers.

How Is Japan Responding?

Reports suggest that the Ministry of Finance is considering reducing long-term bond issuance, which could ease supply-driven selling pressure.

BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda emphasized that sharp moves in ultra-long bond yields could spill over into medium- and short-term yields—potentially disrupting the broader economy. He said the BoJ is closely monitoring market developments.

Market participants widely expect the BoJ to review its bond purchase reduction plan at its mid-June policy meeting.