Trump's Dollar Dilemma: Why a Weaker USD Stings More Now

TradingKey – As the world’s most influential currency, the U.S. dollar impacts economies and political systems globally — directly or indirectly. During Donald Trump’s second term in office, efforts to reduce trade deficits have clashed with attempts to preserve the dollar’s global dominance, leading to conflicting narratives around whether the administration favors a strong or weak dollar.

In the later stages of the 2024 U.S. presidential election, potential tariff policies and Trump’s rising chances of winning fueled a "strong dollar" narrative. However, during the first five months of the Trump 2.0 administration, the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) plummeted to its worst historical performance, prompting Wall Street to shift toward a consensus on a "weak dollar."

Given America's overall strength and the long-standing dominance of the dollar, a strong dollar often seems like the natural order of things. Historically, many U.S. presidents have favored some degree of dollar depreciation to support export competitiveness.

Yet this time, Trump’s policy mix has given rise to a “Sell America” investment logic. So why is that?

The Global Dominance of the U.S. Dollar

Through institutional pillars like the Bretton Woods system (gold-dollar peg) and the 1970s petrodollar regime (oil priced in USD), the U.S. dollar has reigned as the global reserve currency for decades.

Although the euro, yen, and yuan have gained prominence in a more diversified international currency landscape, none can rival the dollar in terms of liquidity, market depth, or institutional backing.

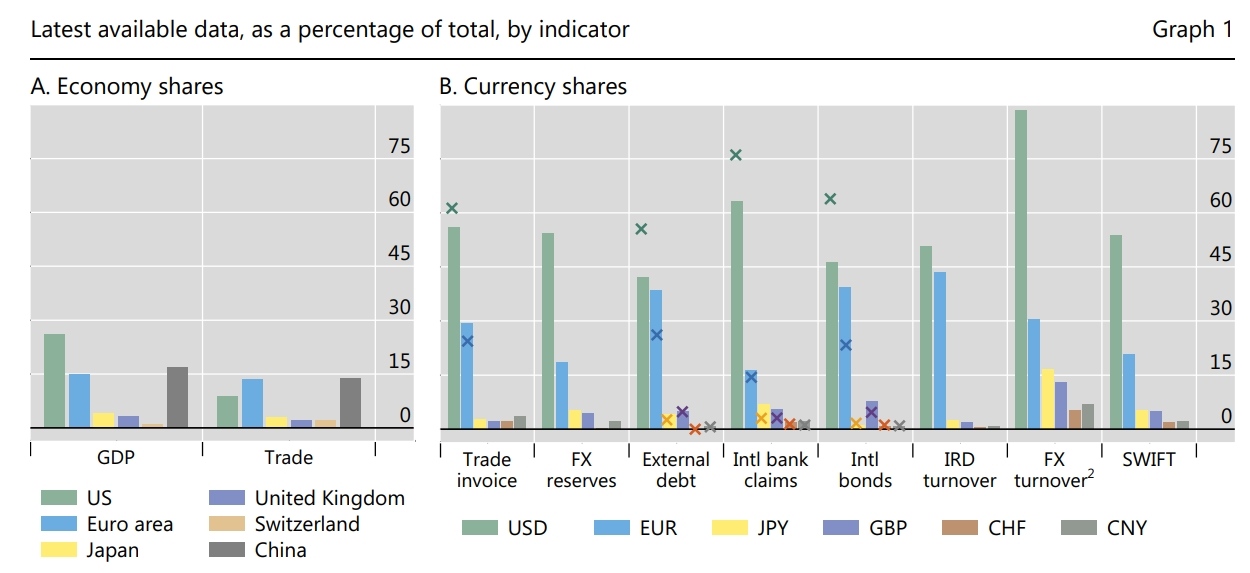

The International Role of the U.S. Dollar, Source: BIS

- Reserve Currency: According to the IMF, the dollar accounts for about 58% of global foreign exchange reserves, compared to roughly 20% for the euro and just over 2% for the Chinese yuan.

- Pricing Benchmark: Major commodities such as oil, gold, and grains are priced in dollars.

- Payment Currency: SWIFT data shows that the dollar makes up about 50% of global payments, followed by the euro at 22%.

- Safe-Haven Asset: The dollar, often tied to U.S. Treasury bonds, is traditionally seen as a safe-haven asset, especially during times of economic or geopolitical turmoil — such as during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

Despite recent trends toward de-dollarization driven by the rise of the euro, BRICS expansion, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the dollar remains remarkably resilient.

What Do Strong and Weak Dollars Mean?

The strength or weakness of the U.S. dollar is typically measured by the Dollar Index (DXY), which tracks the value of the dollar against a basket of major currencies including the euro, yen, and pound. A weak dollar refers to a sustained period of depreciation, while a strong dollar reflects appreciation.

DXY Dollar Index, Source: Trading Economics

Factors influencing the DXY include:

- Federal Reserve Monetary Policy

- U.S. Economic Performance

- Global Risk Sentiment

A stronger dollar increases the appeal of holding U.S. cash, Treasuries, and equities, drawing capital inflows. Conversely, a weaker dollar reduces returns on dollar assets and may trigger capital outflows.

From a trading perspective:

- Strong Dollar makes imports cheaper and supports U.S. consumerism.

- Weak Dollar boosts exports by making American goods more affordable abroad.

Historically, U.S. governments have sometimes deliberately weakened the dollar to stimulate exports — such as under the Plaza Accord (1985) or the potential Mar-a-Lago Accord.

Does Trump Want a Strong or Weak Dollar?

This question doesn’t have a simple answer. Trump’s policy signals have been mixed.

Some argue that no U.S. president fundamentally wants a strong dollar — they all ultimately prefer a weaker currency to boost exports and reduce trade deficits. Yet Trump’s administration has sent conflicting messages.

On one hand, Trump aims to reduce the massive U.S. trade deficit that has grown over the past half-century, suggesting a preference for a weaker dollar to enhance export competitiveness. On the other hand, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has reaffirmed the traditional U.S. commitment to a strong dollar policy.

A weaker dollar not only benefits exporters but also represents a form of “hegemonic depreciation” — reducing the purchasing power of foreign-held dollar reserves, giving the U.S. leverage over foreign policy, and lowering the real burden of U.S. debt.

Trump once warned that losing the dollar’s global reserve status would be akin to losing a war.

Why Is a Weak Dollar More Painful Now?

Past U.S. administrations have successfully engineered dollar depreciation without triggering systemic instability. For example, during George W. Bush’s presidency, a weaker dollar boosted agricultural and manufacturing exports. Under the Biden administration, fiscal stimulus and accommodative monetary policy led to a softer dollar, yet the economy remained robust.

However, Trump’s attempt to pursue both a strong and weak dollar simultaneously has created a paradox — what analysts call the “dollar dilemma.”

Rather than reinforcing the dollar’s global role, Trump’s policies have undermined confidence in it:

- Record-high tariffs

- Threats to Federal Reserve independence

- Tax proposals like the potential Section 899 Foreign Asset Tax

These inconsistent and unpredictable moves have shaken investor trust.

Deutsche Bank analysts warn that U.S. policies are accelerating global de-dollarization. Morgan Stanley projects that by mid-2026, the DXY could fall from around 100 to 91, a 9% decline.

The shift from a strong to a weak dollar narrative has been accompanied by repeated episodes of triple losses in U.S. stocks, bonds, and the dollar itself — a pain rooted in internal contradictions within U.S. economic policy and waning confidence among global investors.

How Is the World Preparing for a Weaker Dollar?

As the dollar weakens, capital flows have shifted toward European, Japanese, and select Asian markets. Eurozone bonds have gained popularity, and gold has re-emerged as a favored hedge.

Morgan Stanley notes that non-U.S. investors are reassessing their exposure — not just to U.S. assets, but to the U.S. dollar itself.

Wells Fargo sees a medium-term trend forming around a weaker dollar. JPMorgan recommends increasing allocations to the yen, euro, and Australian dollar, while Morgan Stanley identifies the euro, yen, and Swiss franc as potential beneficiaries of dollar depreciation.

At the end of May, ECB President Christine Lagarde issued a challenge to the dollar’s dominance, calling for Europe to strengthen the foundations of the euro’s global use — geopolitical, economic, and legal — to elevate its international standing.