Grab Gold’s New Story After Big Swings

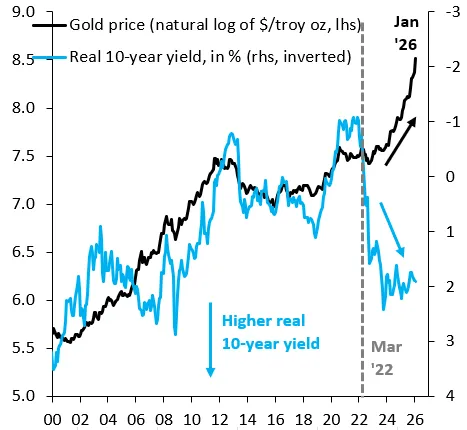

The Fading Power of the Rate Story

TradingKey - For decades, gold’s (XAUUSD) inverse link to real interest rates was one of the cleanest trades in macro. When real yields rose, gold usually fell—after all, the metal pays no interest, so higher rates raise its opportunity cost. That logic, however, has broken down in striking fashion. The market is no longer fixated on “carry costs”; it’s focused on something deeper—whether governments can still service their debts at all, and whether they’ll resort to inflation or devaluation to do it. The heavier the public‑debt load and the weaker the fiscal discipline, the higher the eventual price in rates, currency, and credit.

Gold is evolving—from a cyclical asset driven by rates to a structural hedge against debt and credit stress. Even if short‑term pullbacks emerge, the combination of high leverage, heavy budget deficits and intensifying geopolitics argues that gold now holds a more strategic place in global portfolio construction than at any point in recent decades.

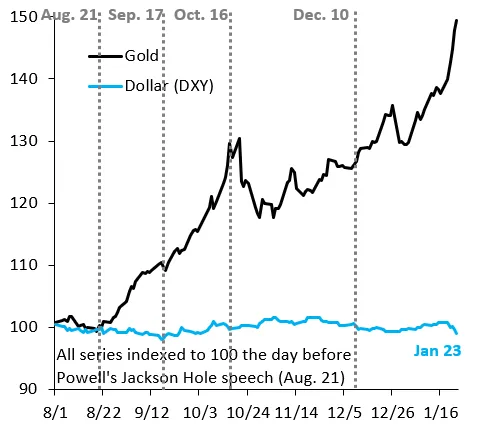

The Dollar Story Deepens

Historically, one of the oldest macro pair‑trades is simple: the dollar down, gold up. A weaker dollar undermines the appeal of dollar‑denominated assets such as Treasuries and U.S. equities, prompting capital to rotate into hard assets or non‑dollar exposures—the classic “de‑dollarization” trade.

By late 2025 the greenback had stabilised, at times even strengthened, yet markets were already leaning into a bet that its next long‑term move would be lower. Early 2026 confirmed that view: the dollar began to slide decisively. That shift layered a traditional tailwind for gold on top of the existing narrative of debt and monetary‑system anxiety. For non‑U.S. money, buying gold suddenly felt like buying insurance at a discount. The result: faster rotation out of dollars and into gold, amplifying both the price momentum and the psychology of a crowded currency unwind.

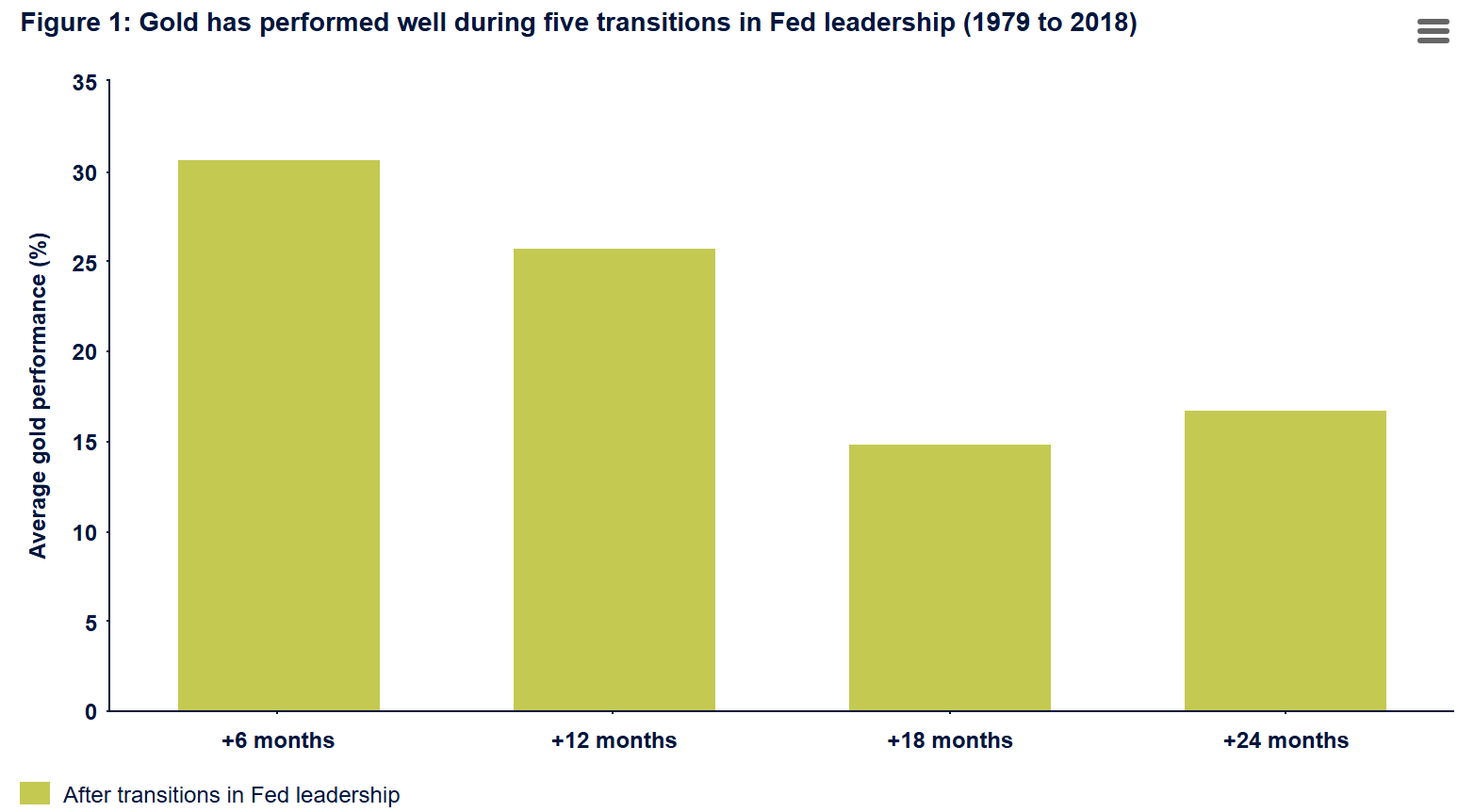

The Federal Reserve Variable

Whenever the Federal Reserve changes leadership, markets spend the following year or two recalibrating expectations—testing how the new chair balances inflation tolerance against growth and financial‑stability risks. History offers a precedent: in 1979, gold rallied strongly in the 6–24 months after the Fed’s transition.

The incoming chair, Kevin Warsh, has long questioned quantitative easing and the swollen Fed balance sheet. Investors expect that even if he cuts rates, he will be reluctant to restart large‑scale asset purchases or suppress long‑term yields artificially. That stance implies tighter liquidity and a steeper curve. Not surprisingly, the initial repricing slammed the overleveraged bullish trades in gold and silver built around perpetual debasement.

Yet gold’s defensive role hasn’t disappeared. It has simply shifted—from an extreme, one‑way melt‑up to a volatile high‑plateau phase more anchored in fundamentals. As liquidity expectations reset, the metal’s function as a hedge rather than a momentum chase reasserts itself.

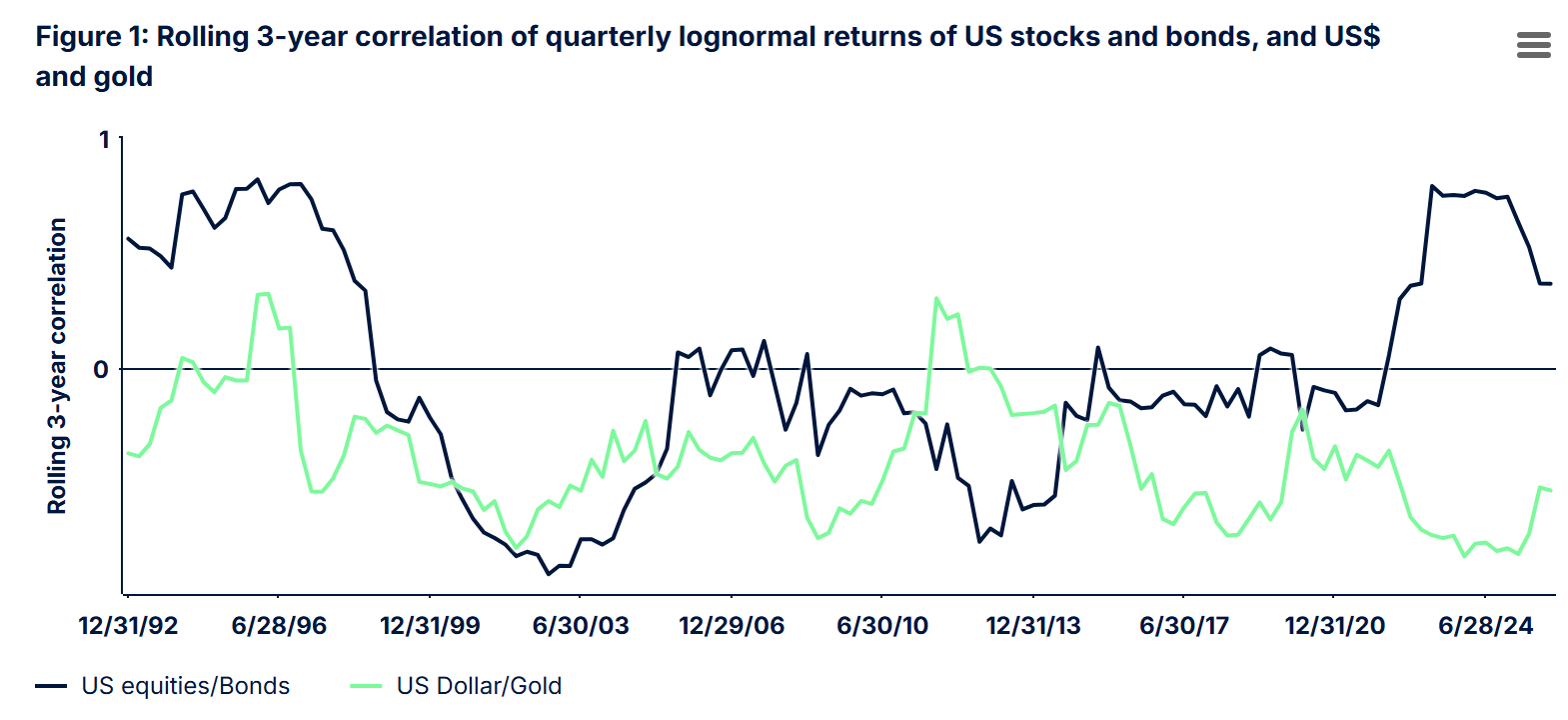

Hedging Duration Risk

High debt and sticky inflation are forcing long‑dated yields higher, repeatedly tugged between market pressure and policy intervention. The result: wider swings in 10‑ to 30‑year Treasury prices and a resurgence of duration risk once thought negligible. In this world of record leverage and inflation‑driven yield drift, gold is increasingly viewed as an attractive hedge against both duration volatility and currency dilution.

The structural correlations have also shifted. Through the post‑pandemic inflation spike and the Fed’s tightening cycle, the stock‑bond correlation in the U.S. surged to three‑decade highs. In that new environment—high debt, rising duration risk, stronger stock‑bond linkage, and an accelerating de‑dollarization trend—long Treasuries no longer offer a reliable “risk‑free return.”

Central banks and institutions are responding in kind, elevating gold as the third pillar of portfolio defense: a counterweight to equity drawdowns, to bond‑price swings, and to the slow erosion of fiat credibility itself.